- Picture Book Maker(s)

- Posts

- Walter Crane

Walter Crane

Trailblazer of the Golden Age of Picture Books

Walter Crane was at the center of the transformation of children’s books from simple and cheap books to stunning works of art filled with detailed patterns, textiles and designs. His innovative approach not only captivated young readers but also challenged the notion that picture books were pointless amusements.

The Golden Age of Children's Literature emerged because of advances in the marketing of children's books and printing. Edmund Evans and George Baxter helped revive wood engraving and utilized it in publishing. The advances enabled the mass production of books at lower costs while showcasing revolutionary artwork. This increased access to a broader audience. The rise of the middle class also helped. Parents increasingly prioritized education and literacy for their children. John Newbery also proved earlier in the 19th century that picture books were profitable, and this new market was growing ever since.

During this time, there was an increase in the production of high-quality literature intended for children. This era is marked by a departure from static and moral-focused stories. Stories turned toward more imaginative and emotionally engaging stories. These stories captured the minds of children then, and continue to capture them today. This is the first of a trilogy of artists that were key factors in revolutionizing picture books into what we think of when we hear the phrase ‘children’s book’.

"Let the designer lean upon the staff of the line - line determinative, line emphatic, line delicate, line expressive, line controlling and uniting."

Walter Crane, born in 1845, was an English illustrator, painter, and designer best known for his illustrations in children’s books. He was the son of the portrait painter and miniaturist Thomas Crane (1808–59). At a young age, Walter would decorate books with watercolors for amusement. Thomas saw potential in his son. He introduced him to the wood engraver William James Linton. Linton headed one of England's top printing and engraving companies.

From 1859 to 1862, he apprenticed under Linton in London. Crane's experiences while working with Linton, who was not only a master engraver and writer but also a champion of political freedom, were formative for developing Crane's social awareness. One of Crane's chief duties was to copy drawings on the wood, both his own and those of other artists. This practical introduction to the craft of illustration helped him throughout his career. Linton also sent Crane to study the animals at the Zoological Gardens, where Crane learned the importance of spontaneous line. Animals remained his favorite subjects. During this time, he also got to study the works of the Italian old masters. He also studied contemporary artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Millais.

In 1863, he finished his apprenticeship. Just after, he met Edmund Evans, the color printer, who wrote in his journal,

"I availed myself of Walter Crane's talent at once: he did all sorts of things for me—he was a genius. The only subjects I found he could not draw were figure subjects of everyday life."

His first work with Edmund Evans began with designs for yellow-backs, an increasingly popular format of cheap novels. These mass-produced books were bound between straw boards, with yellow glazed paper and a picture printed in color on the covers.

In 1865, Evans saw the potential of Crane’s art for the growing children’s book market. He suggested Crane’s illustrations to the British publisher Frederick Warne for his Sixpenny Toy Book Series. He also suggested a similar series for Routledge in America. The books were very successful. They were still being issued in bound collections decades after they first appeared.

Crane illustrated thirty-seven toy books over ten years, generally with traditional or Fairy tale story texts. In all, Crane designed more than 50 toy books. People teasingly called him the "academician of the nursery." Crane illustrated fairy tales with the same careful detail he had put into his Academy paintings. He revolutionized public views of children’s books. Before Crane, they were seen as simple, cheap paperbacks. His illustrations featured detailed patterns, textiles, clothing, and furniture designs. Crane himself acknowledged that he used picture books as a platform to express his broader ideas about furniture and decoration.

Crane believed that good art and design could make books interesting to children. They could help children to learn to read from a very early age. He saw that every part of the book can encourage children to enjoy reading. This includes the covers, endpapers, titles, pictures, type, and page layout. Crane took the work of making children's books very seriously; writing in later life:

"We all remember the little cuts that colored the books of our childhood. The ineffaceable quality of these early pictorial and literary impressions affords the strongest plea for good art in the nursery and the schoolroom."

He also saw the special appeal of children's books. They appealed to artists of his generation, as he wrote,

"They are attractive to designers of an imaginative tendency, for in a sober and matter-of-fact age they afford perhaps the only outlet for unrestrained flights of fancy open to the modern illustrator, who likes to revolt against the despotism of facts."

Eastern Inspiration

Crane's artistic style underwent a significant transformation in 1898 when he discovered the beauty and simplicity of Japanese prints. He wrote,

“Their treatment, in definite block outline and flat, brilliant, as well as delicate colors, struck me at once and I endeavored to apply these methods to the modern fanciful and humorous subjects of the children's toybooks and the methods of wood-engraving and machine printing.”

By incorporating elements such as bold outlines, flat colors, and asymmetrical compositions, Crane created a unique and striking visual style that set his work apart from other children's book illustrators of the time. This fusion of Eastern and Western aesthetics revolutionized the appearance of children's books and inspired countless artists who followed in his footsteps.

Crane also filled the whole picture frame. He used clear lines and bold blacks. He cared for detail in decoration, dress, and furniture. He wanted the text to blend with the pictures, and frequently illustrated a part of the text. Crane's intensity for his art can largely be attributed to his embracing of the arts and crafts movement and political affiliations.

The Work of Walter Crane with Notes by the Artist - I could not find an online copy to share, check your local library.

Use Your Hands

"We desired first of all to give opportunity to the designer and craftsman to exhibit their work to the public for its artistic interest and thus to assert the claims of decorative art and handicraft to attention equally with the painter of easel pictures, hitherto almost exclusively associated with the term art in the public mind. Ignoring the artificial distinction between Fine and Decorative art, we felt that the real distinction was what we conceived to be between good and bad art, or false and true taste and methods in handicraft, considering it of little value to endeavour to classify art according to its commercial value or social importance, while everything depended upon the spirit as well as the skill and fidelity with which the conception was expressed, in whatever material, seeing that a worker earned the title of artist by the sympathy with and treatment of his material, by due recognition of its capacity, and its natural limitations, as well as of the relation of the work to use and life."

Crane admired the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the teachings of the art critic John Ruskin. From the early 1880s, Crane was influenced by his friend William Morris. He became deeply involved with the Socialist movement, playing a big role in adding art to the daily lives of people of all social classes. Crane also contributed weekly cartoons to Socialist publications; Justice, Commonweal, and The Clarion. Additionally, he dedicated much of his time and effort to the Art Workers Guild. He was its Master in 1888 and 1889. He also spent time with the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, which he helped start in 1888.

Crane's involvement in the Arts and Crafts movement played a significant role in shaping his approach to book design. As a key figure in the movement, Crane embraced its core principles of craftsmanship, simplicity, and the unity of art and function. These values are evident in his meticulous attention to every aspect of his books, from the intricate illustrations to the carefully chosen typography and harmonious page layouts. By applying the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement to children's literature, Crane created books that were not only visually stunning but also exemplified the belief that beauty and utility could coexist in everyday objects.

Crane's work was diverse. It included easel paintings, plaster reliefs, tiles, stained glass, pottery, wallpaper, and textile designs. Throughout these endeavors, he stuck to the principle of good design and craft. He was vital in the movements to renew these standards. This background as a painter and his commitment to artistic excellence blurred the lines between fine art and illustration. His detailed, expressive, and beautifully composed illustrations brought a new level of artistic merit to children's books, challenging the traditional hierarchy that placed fine art above applied arts. Crane's work demonstrated that illustrations could be just as powerful, emotionally resonant, and technically sophisticated as paintings hung in galleries. By elevating the status of illustration, Crane paved the way for future generations of artists who would continue to push the boundaries of what was possible in the medium.

A friend (C. R. Ashbee) paid tribute to him at his death in 1915. He said that Crane remained naive and childlike. Crane chose to live in a fairy-tale world, not in 'humdrum' reality. Even the most childlike of his little weaknesses, writes Ashbee, "was of the fairy-tale type. He called himself 'Commendatore Crane' because the king of Italy had once given him a title for arranging the Arts and Crafts exhibition ...He just loved being an 'official', but he was so fundamentally 'unofficial' that nobody minded ... nobody could possibly hurt Crane."

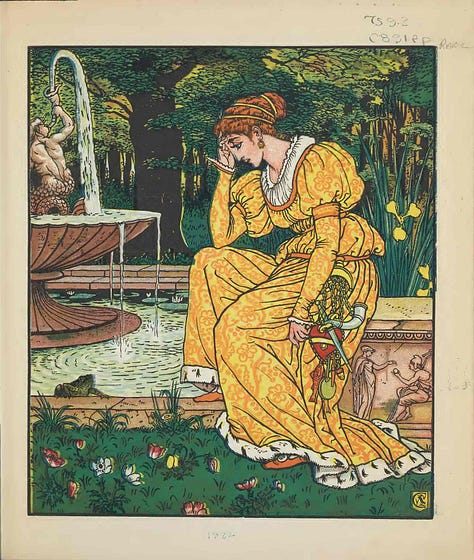

The Frog Prince

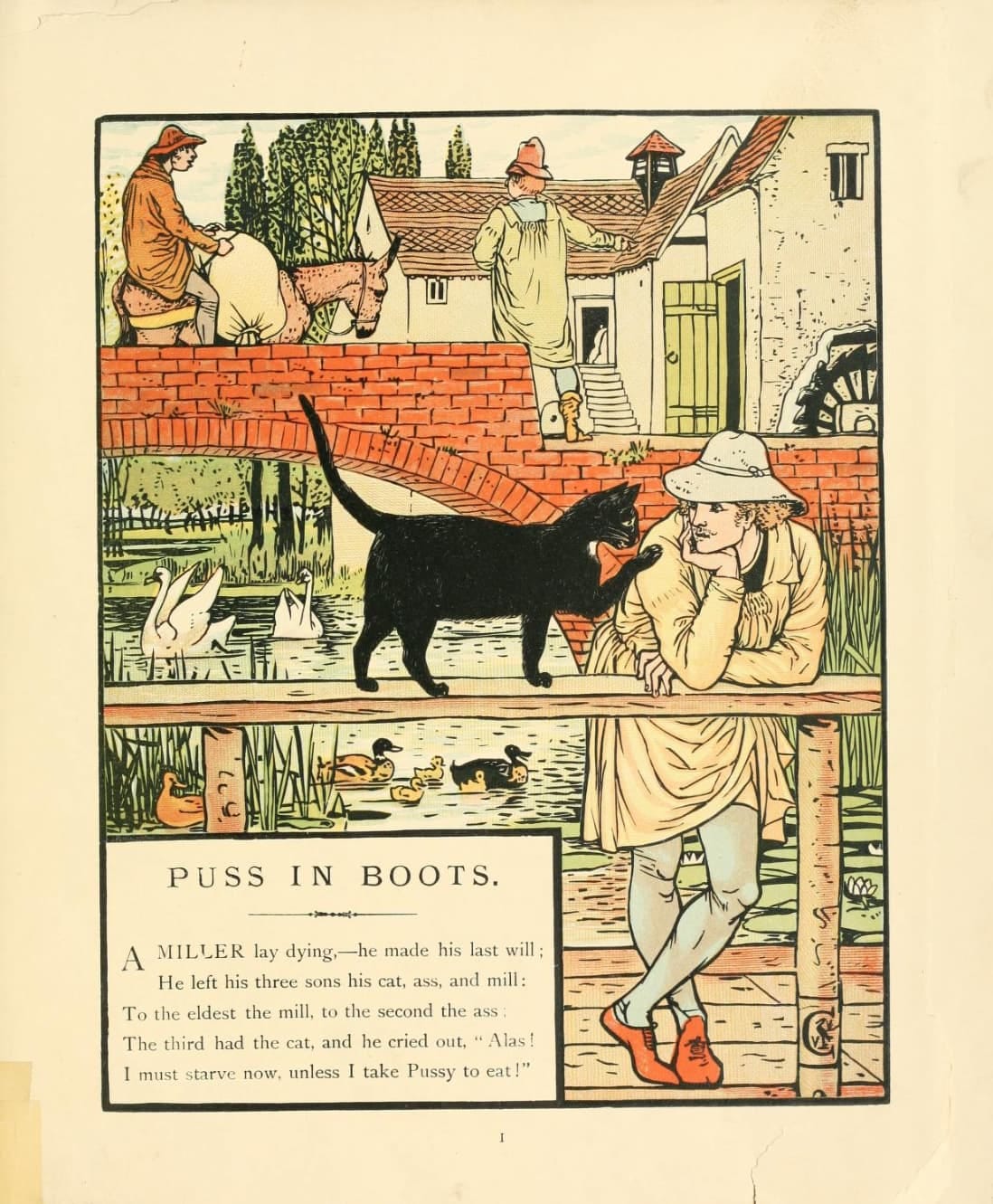

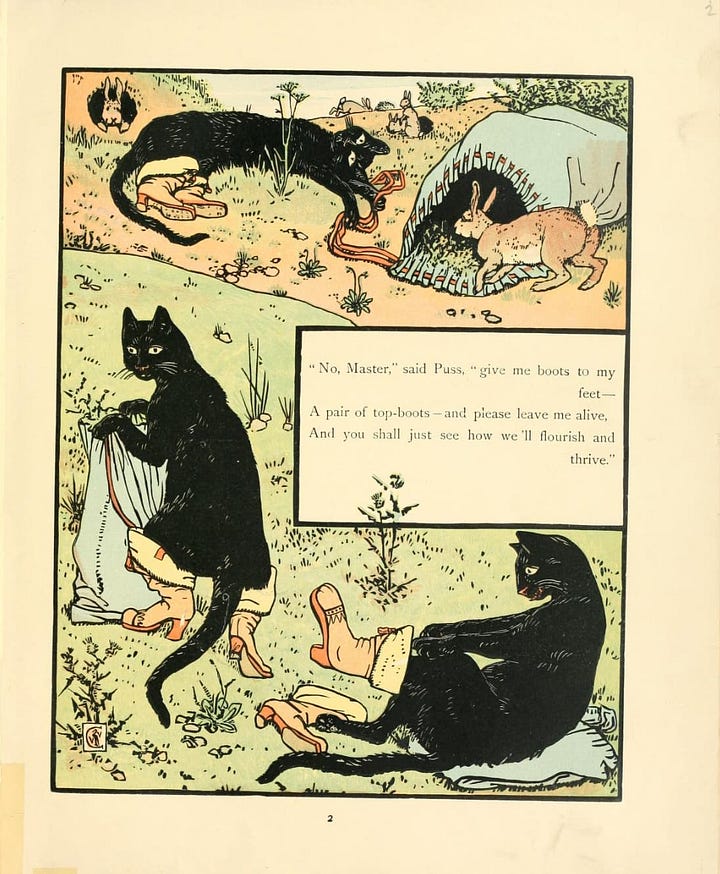

Puss in Boots

Cranes work for Puss in Boots is some of my favorite. For the time period it is fresh and unique and showcases the obvious influence of Japan on Crane. The most immediately noticeable aspect of these illustrations is Crane's bold use of black. No longer strictly utilized in outlines, black becomes a dominant color in its own right, creating strong silhouettes and dramatic contrasts. This technique, directly inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, lends a powerful graphic quality to the images. The cat's sleek form, often rendered in solid black, stands out against lighter backgrounds, directing the readers attention around the illustration and emphasizing the character's place in the composition. Crane also beautifully balances out the black cat with washes of black in the background to balance out the image and create great depth and ultimately prevents the cat from sticking out in the illustrations.

Crane's composition in these illustrations also bears the hallmark of Japanese influence. He employs asymmetrical layouts and unexpected viewpoints, breaking away from the more traditional, centered compositions of Western art. This approach creates a sense of dynamism and movement, perfectly suited to the adventurous nature of the Puss in Boots story.

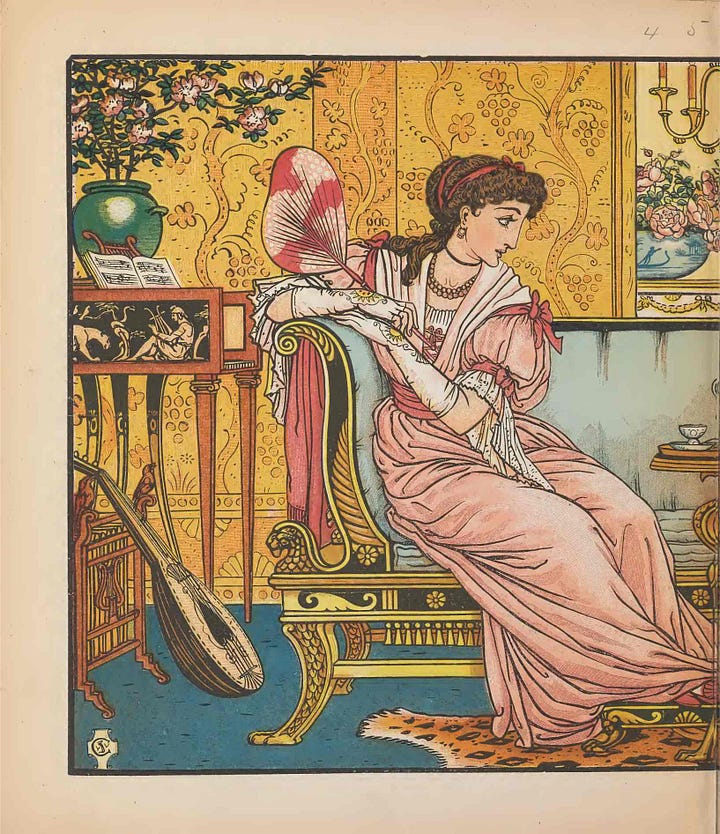

The Beauty and the Beast

In Crane's interpretation of "Beauty and the Beast," the Beast is portrayed as a boar-like creature with enormous teeth and a trunk-like snout. However, Crane's artistic genius shines through in his ability to render this potentially scary character approachable and even endearing to young readers. Despite the Beast's wild appearance, Crane illustrated him with ‘perfect’ posture and dresses him in magnificent clothing, effectively humanizing the character, even if he is a wild boar.

This transformation of the extraordinary into the ordinary is further exemplified in the scene where the Beast sits with Beauty on an elegant and detailed sofa. Here, the Beast is drawn in a relaxed pose, wearing a monocle and holding a fashionable hat in his hoof. By exaggerating the Beast's human qualities, Crane invites readers to imagine this fantastical character within the familiar context of Victorian Britain. The juxtaposition of the Beast's otherworldly appearance with his very Victorian attire and surroundings serves a dual purpose. It not only blurs the line between reality and fantasy but also injects a subtle humor into the illustrations. This approach allows something that could be terrifying and overwhelming for a younger view to be digestible but also with a hint of enough otherworldly feeling to cause an eerie but comforting image.

Crane's attention to detail doesn’t just stop with the look of the beast, but also in everything else, like the wallpaper, the furniture and every tiny knick knack. His use of patterns and textures cover every inch of every illustration/composition, yet they rarely overwhelm or become cluttered. Each composition gives the sense that even the patterns and out of focus elements of every illustration demanded the same respect as the main character. Everything in the composition is coming together to dance with the eye of the viewer and move the viewer around the page to further tell the story. It was this attention to every detail that allowed Crane to stand out from many artist of the time.

The impact of Walter Crane's innovations in children's book illustration can be seen in the work of numerous artists who followed in his footsteps. The Golden Age of Illustration, which flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, owes much to Crane's pioneering work in elevating the artistic standards of children's books. Today, over a century after his death, Crane's legacy continues to inspire illustrators around the world who strive to create books that are both visually stunning and emotionally engaging for young readers.

Reply