- Picture Book Maker(s)

- Posts

- Thomas Bewick & Edmund Evans

Thomas Bewick & Edmund Evans

A Colorful Transformation

In an age where digital media dominates, it is easy to forget the intricate wood engravings and vibrant color prints that brought books to life centuries ago. But the story of Thomas Bewick and Edmund Evans, two pioneers of wood engraving and color printing, reminds us of the enduring and lasting effect of the printed images. Without these two men, the world of picture books would look very different today. Through groundbreaking techniques and artistic vision, these two led the way for the modern picture book and the way it forever changed storytelling for not just children but adults too.

Thomas Bewick

“The first and greatest of all Britain’s naturalist-illustrators, the British Audubon”

During the Victorian period, book illustration gained popularity. This was supported by the work of wood engravers. Woodcut extended back centuries in Europe and further in Asia. Typically, the carver left the parts to be printed in black in relief. This allowed illustrations to be printed with the text. Thomas Bewick rediscovered the technique in the 18th century. He perfected the process that was used a lot in the 19th century. It needed hardwood blocks and tools for metal engraving. The preferred method of relief engraving had been to work with the grain on the plank side of a block. However, Bewick carved the end of the block and against the grain using a burin. He also used parallel lines instead of cross-hatching. This let him achieve a wide range of tones and textures. Bewick passed his techniques to apprentices. These included Ebenezer Landells, who passed them to Edmund Evans.

Into the Wood

Thomas Bewick, a printmaker and illustrator, was born in 1753 in Northumberland. He was vital in reviving the art of wood engraving and making it a major printmaking technique. Being the eldest of eight children, Thomas was expected to help around the farm and the colliery as a boy. But he loved the countryside around him, often leading him to skip his tasks. He loved to roam, fish, look at flowers, and watch birds and animals. These experiences would later prove to have a significant influence on his work in life. When he was 14 years old, Bewick was apprenticed to a local engraver.

He received his education in the nearby village under the guidance of Reverend Christopher Gregson. At the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed to Ralph Beilby, the proprietor of a nearby engraving business. Throughout his seven-year apprenticeship, Bewick was trained in all facets of the engraving trade. Beilby quickly saw his young apprentice's great talent for woodcut engraving. He assigned him to make many book illustrations, including ones for children's books.

The Bewick Art of Engraving

Bewick's art is seen as the peak of wood engraving. He refined the technique by carving against the grain of hard boxwood (Traditional woodcuts cut along the grain) with fine tools used by metal engravers. This method allowed for more detail and durability. Wood engraving is inked on the surface. It requires low pressure to print and allows the blocks to be reused with text in the same process. Copper plate engravings, in contrast, required separate printing due to their intaglio technique.

Bewick observed nature with care. He had a great visual memory and sharp eyesight. These qualities let him show precise and complex details in his engravings. This precision conveyed characters with humor and emotion. Achieved by using varying groove depths for different shades of grey and distinct patterns for textures. However, this subtlety posed challenges for printers. They needed to use precise ink and careful handling to meet Bewick's high standards. This made the process slow and costly.

Despite the technical demands and the fact that readers needed magnifying glasses to fully appreciate his tiny illustrations,Bewick's engravings gained wide acclaim. They established wood engraving as the main method of book illustration for a century.

Apprentice Discovery

After completing his apprenticeship, Bewick loved his new freedom. He called it "a time of great enjoyment" in his Memoir. He promptly booked passage on a collier bound for London upon returning to Newcastle. He was eager to try his luck in the bustling city. However, despite its business potential, he found London unpleasant. He soon returned home to Newcastle. In 1777, he rejoined Ralph Beilby as a partner and took on Beilby's younger brother John as an apprentice. They lived together during this period.

The engraving business thrived. Beilby and Bewick started an ambitious project, the General History of Quadrupeds, published in 1790. This work aimed to inspire youth to study natural history. It was praised for its accurate and vivid depictions of animals. They began work on a companion volume about birds, building on this success. In July 1791, Bewick traveled to Wycliffe Hall near Barnard Castle, the former home of Marmaduke Tunstall, who had a large private collection of stuffed birds, including many rare species, providing valuable research material. At the invitation of William Constable, who had inherited the estate, Bewick spent two months there meticulously sketching many birds. Unhappy with poorly stuffed specimens, they decided to focus the book on British birds. The History of British Birds was published in two volumes: Land Birds in 1797 and Water Birds in 1804. These works showcased Bewick's exceptional skills. He was a keen observer of wildlife. They drew largely from his personal experiences and using specimens sent by friends and admirers.

His bird illustrations were a hit in 1797. So, Bewick quickly started the second volume, Water Birds. But, a dispute over authorship led to a final and bitter split with Beilby in 1798. Bewick was unable to control his feelings and resolve issues quietly. So, the partnership ended turbulently and expensively, leaving Bewick with his own workshop. Bewick kept the engraving business. He then published revised editions of Quadrupeds and British Birds. The business expanded. It started to cover a range of engraving types. This includes work on glass, silver, and copper.

In 1812, Bewick embarked on a new venture that he had long cherished: The Fables of Aesop and Others. This work was eventually published in 1818. He loved fables and moral tales since he was young. They continued to inspire many of his vignettes, which he called "tale-pieces."

Thomas Bewick passed away in 1828 at the age of seventy-five. He left the engraving business to his son Robert. He also left him a large collection of watercolor and pencil drawings, woodblocks, and engravings that the family had carefully gathered over many years.

Bewick revived wood engraving, providing a big advancement in making illustrated books. Unlike copperplate, a wood engraving could be put into a text block and printed with the text all in one press. This made the process much less expensive on several levels. Bewick, a great artist, was notable for his time and for the techniques he taught his apprentice, who then passed them to Edmund Evans.

Edmund Evans

Edmund Evans, an English illustrator, engraver, printer, and businessman, was born in Southwark in 1826. He was famous for his pioneering use of full-color printing and helped develop and popularize it. Soaring in popularity during the 1800s, he teamed with illustrators Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, and Richard Doyle, renowned for their picture book art. Their collaborations resulted in what are now considered classics in children's literature. He is, for many reasons, one of the most influential persons in the history of picture books. He created a whole new market for children's books, which existed before his time, but became a huge business only after color printing improved with his skill and eye for print. He was very involved in developing marketing and distribution for picture books and was one of the first printers who started promoting illustrators. Before this, they were treated as inferior to "real" painters.

At age 13, he left school. He was apprenticed to a printing house as a "reading boy", essentially a proofreader. But his stutter led to him being demoted to running errands. Despite being worked long hours from seven in the morning to ten at night, young Evans found the printing processes at the firm fascinating. He was particularly drawn to the methods for copying illustrations and began to teach himself drawing. The owner of the printing firm noticed Evans's budding talent and arranged for Evans to be apprenticed to a renowned engraver, Ebenezer Landells.

A Delicate Process

In the 1830s, George Baxter made color relief printing popular again, known as chromoxylography. He did this by using a background detail plate printed in aquatint intaglio. Then, he used colors printed in oil inks from relief plates—usually wood blocks. Evans followed the Baxter process with the exclusive use of Bewick-style carved wood blocks.

Evans' process involved quite a few steps. First, an illustration's line drawing was engraved onto a block. This was done by a photo of a line drawing on a block, or the artist drawing the illustration in reverse or onto the block directly. In other cases, the printer copied the illustration from a drawing. Then, the line drawing was engraved. The illustrator would then color the key block proofs. Next, Evans sequenced them. He registered them precisely to replicate the artist's original as closely as possible. Each color had its own painted and engraved block. A proof of each color block was made before a final proof from the key block. Ideally, the proof would be a faithful copy of the original drawing. But, Evans believed a print was never as good as a drawing. He took care to grind and mix his inks so they imitated the originals as closely as possible. Finally, each block was placed to let the colors print as intended. He was aware of costs and printing efficiencies, so he used as few colors as possible. Illustrations used a base of black, along with one or two colors and a flesh tone for faces and hands. In some cases, Evans may have used just four color blocks: likely black, flesh, and two primary colors. Adding yellow allowed him a greater range. Each color was printed from a separate engraved block; there were often five to ten blocks. The main problem was to keep the correct alignment. This was done by placing small holes in precise spots on each block to which the paper was pinned. If done right, the colors match, but occasional ink squash was visible on the edges of an illustration. Books printed by Evans have been reproduced using some of the original blocks, having "remained in continuous use for over a century".

Evans' skill as a colorist is shown by his use of color and his ability to create subtle tones. His work was distinctive because of the quality of the wood carving and his way of limiting ink, made for a more striking result.

Life After Apprenticeship

He finished his apprenticeship in 1847 at age 21. Evans turned down a job offer from Landells and ventured into business as a wood engraver and color printer instead. Starting out with book cover illustrations and a commission for the Illustrated London News, he later fulfilled orders for book covers and his first commission to print a book. However, the publication stopped using him because they thought his wood engravings were too detailed for newspapers. His final print for them, illustrated by Foster, depicted the four seasons. In fact, Foster received his inaugural commission from publisher Ingram, Cook, and Company to recreate these scenes in oil. This final project eventually led to Ingram selecting Evans for further prints.

Evans' growing business let him apprentice his younger brothers, Wilfred and Herbert. It also allowed him to purchase a hand press. Shortly afterward, he moved to Racquet Court. There, he expanded his operations by buying three more hand presses.

In the early 1850s, Evans pioneered the design of book covers known as yellow-backs. They were books bound in yellow-glazed paper over boards. Because he disliked how white paper book covers would easily soil and discolor, Evans developed the yellow-back concept. To remedy this, he experimented with treating yellow paper before adding printed illustrations. Yellow-backs were often reprints or unsold editions, making them a practical solution for publishers. People also called them other names: "Penny dreadfuls," "railway novels," and "mustard plasters." He perfected this method and quickly became the top choice for many London publishers. By 1853, he had established himself as the chief yellow-back printer in the city.

Evans collaborated with renowned artists for the illustrations of these covers, including George Cruikshank, Randolph Caldecott, and Walter Crane. His early covers were brightly colored, primarily using reds and blues. He continued to innovate, engraving in gradation to make lighter tints, especially for faces and hands. He used blue blocks over black to add textures and patterns. Evans recognized that good cover art could greatly improve the appeal of books, especially true for books that had not sold well at first.

By 1856, Evans had perfected a process of color printing from wood blocks. He became the top wood engraver and best color printer in London.

From Toys to Gold

Critics regard Evans' most important work to be his prints of children's books, which started as 'Toy Books' in the latter part of the century. He made these with Walter Crane, Kate Greenaway, and Randolph Caldecott. Together they revolutionized children's publishing.

In 1865, Evans agreed to print toy books with the publishing house Routledge and Warne. These were paperbound books of six pages, to be sold for sixpence each. Toy books revolutionized children's books and made Evans popular among children's book illustrators. The toy book market grew so much that he began to self-publish and hire artists. When the demand became too much, he hired other engraving firms to fill the orders.

"The most memorable body of illustrated books for children in the latter half of the nineteenth century came from the presses of the gifted London printer Edmund Evans. When Evans perfected a process of color printing from wood blocks in 1856, he invited three artists of the day to join him in producing a series of picture books for children, known as toy books. Those three artists were Kate Greenaway (1846-1901), Randolph Caldecott (1846-86), and Walter Crane (1845-1915). They have come to be looked upon as the founders of the picture-book tradition in English and American children's books."

Working with Gold

Walter Crane

“Mr. Edmund Evans was known for the skill with which he had developed colour-printing applied to book illustration, and I was fortunate in being thus associated with so competent a craftsman and so resourceful a workshop as his.”

In 1863, Evans enlisted Walter Crane to illustrate "yellow-back" novels. Their collaboration expanded in 1865 to include toy books of nursery rhymes and fairy tales. This venture continued with two to three new titles each year until 1876. At first, Crane's designs featured simple red and blue colors with black or blue for key blocks. Over the years, Crane illustrated 50 toy books. Evans engraved and printed them between 1865 and 1886. They made Crane a leading children's book illustrator in England.

Crane developed his designs on the blocks. Over time, he added more intricate details, influenced by Japanese prints (known for their clear outlines and bright colors). In 1869, Evans added yellow to their palette, expanding the range of hues used with red and blue. Crane further refined his illustrations with meticulous attention to detail, focusing on things like furniture and clothing.

During Crane's absence abroad from 1871 to 1873, Evans continued to make his illustrations. He managed this process through mail. Their collaboration peaked in 1878 with The Baby's Opera, which featured intricate pages and borders. Initially, they printed 10,000 copies, but they quickly printed more due to popular demand.

Randolph Caldecott

The fast production pace led Walter Crane to halt work for a short time. This prompted Edmund Evans to turn to Randolph Caldecott. Caldecott's magazine illustrations had impressed Evans. Evans initially hired Caldecott to illustrate nursery rhyme books. Their first was a new edition of The House that Jack Built in 1877. Evans suggested filling each page with illustrations, often simple outlines. This was to avoid the usual blank pages in toy books of that time. From 1878 to 1885 Caldecott illustrated two books a year, establishing himself as a prominent illustrator. These releases were timed for the Christmas market, with print runs sometimes reaching 100,000 copies. Later, collected editions of four works were published in single volumes. Over this time, Evans and Caldecott made 17 books that reshaped children's literature.

Caldecott's method involved making pen and ink illustrations on plain paper. Then, these were photographed onto woodblocks for Evans to engrave. Then, they were copied, using up to six blocks to achieve delicate, multi-color images. Tragically, in 1886, Caldecott died from tuberculosis. The next year, Evans produced a compilation of Caldecott's picture books, The Complete Collection of Pictures & Songs. Remarkably, into the 1960s, reprints of The House that Jack Built were still being made from the original woodblock plates.

Kate Greenaway

In the late 1870s, Kate Greenaway was known for her work on greeting cards. She convinced her engraver father to show Edmund Evans her book, a manuscript of poetry and illustrations titled Under the Window. Evans was impressed by the originality of Greenaway's drawings and verse, so he bought the rights and had an initial edition of 20,000 copies printed. Publishers doubted printing so many copies of a six-shilling book. However, it sold out quickly, which led to continuous reprints until the total reached 70,000 copies.

Under the Window jump-started Greenaway's successful career as an author/illustrator of picture books when it was published in 1879. Evans paid Greenaway outright for her artwork and also offered her royalties on future sales, solidifying their partnership. He carefully photographed her drawings onto woodblocks and then engraved them with great attention to detail. He used color blocks to make vibrant illustrations in red, blue, yellow, and flesh tones, the same process he utilized for many of the illustrators he worked with.

In the 1880s, Evans and Greenaway made two to three books each year. Evans's distinctive printing techniques contributed to the lasting popularity of Greenaway's books well into the 20th century. Their partnership went beyond publishing. Greenaway often visited the Evans family, played with their daughters, and maintained a professional relationship with Evans. He was her only engraver and printer throughout her career.

A Lasting Legacy

Diversifying his work, Evans eventually adopted three-color printing. He started with the Hentschel process in 1902.Beatrix Potter requested it for her book "The Tale of Peter Rabbit."

In 1892, Evans relocated to Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. He handed over the printing business to his sons, Wilfred and Herbert. But, the date he stopped wood engraving is unknown. During his final years, he wrote "The Reminiscences of Edmund Evans." He described it as "the rambling jottings of an old man." It provides insights into his era's color printing. Ruari McLean edited it from a typescript released by Evans' grandson in the 1960s. Oxford University Press published this volume in 1967.

Evans died in 1905. His two sons and three daughters survived him and laid him to rest in Ventnor cemetery. In 1953, W. P. Griffith, Ltd., acquired the firm, which is still running today. Evans' grandson Rex became the managing director. Earlier, Evans had offered Beatrix Potter a stake in the company, but she declined because she had just bought a farm in the Lake District. The St Bride Printing Library in London has a large collection of Evans' original engraved wooden blocks.

Evans' work transformed the picture book market at the time and molded it into what we know it today. His work captivated audiences and changed how they viewed the picture book. The picture book began to grow and develop into a new way to tell stories. Picture books were no longer just text with pictures, but were becoming a partnership between text and picture. Each enhanced the other and told stories for children, not preached at them. Without Edmund Evans and his affordable, stunning reproductions, the world would've never known the true capabilities of Caldecott, Crane, Greenaway, and others as they brought forth a picture book golden age.

A Color Revolution

Left art by Walter Crane for Baby’s Opera. Right is print by Edmund Evans.

What I enjoy most about the original is the amount of elements going on in the image. The ducks flapping in the water, the expression of the man in the background and the flow of the dress. In the final print by Edmund the final illustration is enhanced by the addition of line as texture, especially in the dress and sky. The colors were matched very well by Edmund, even capturing some lovely gradients and transition of color. I like how the final color makes the ducks a bit more defined. But, the tones in the skin and ground flatten in Evans's final version.

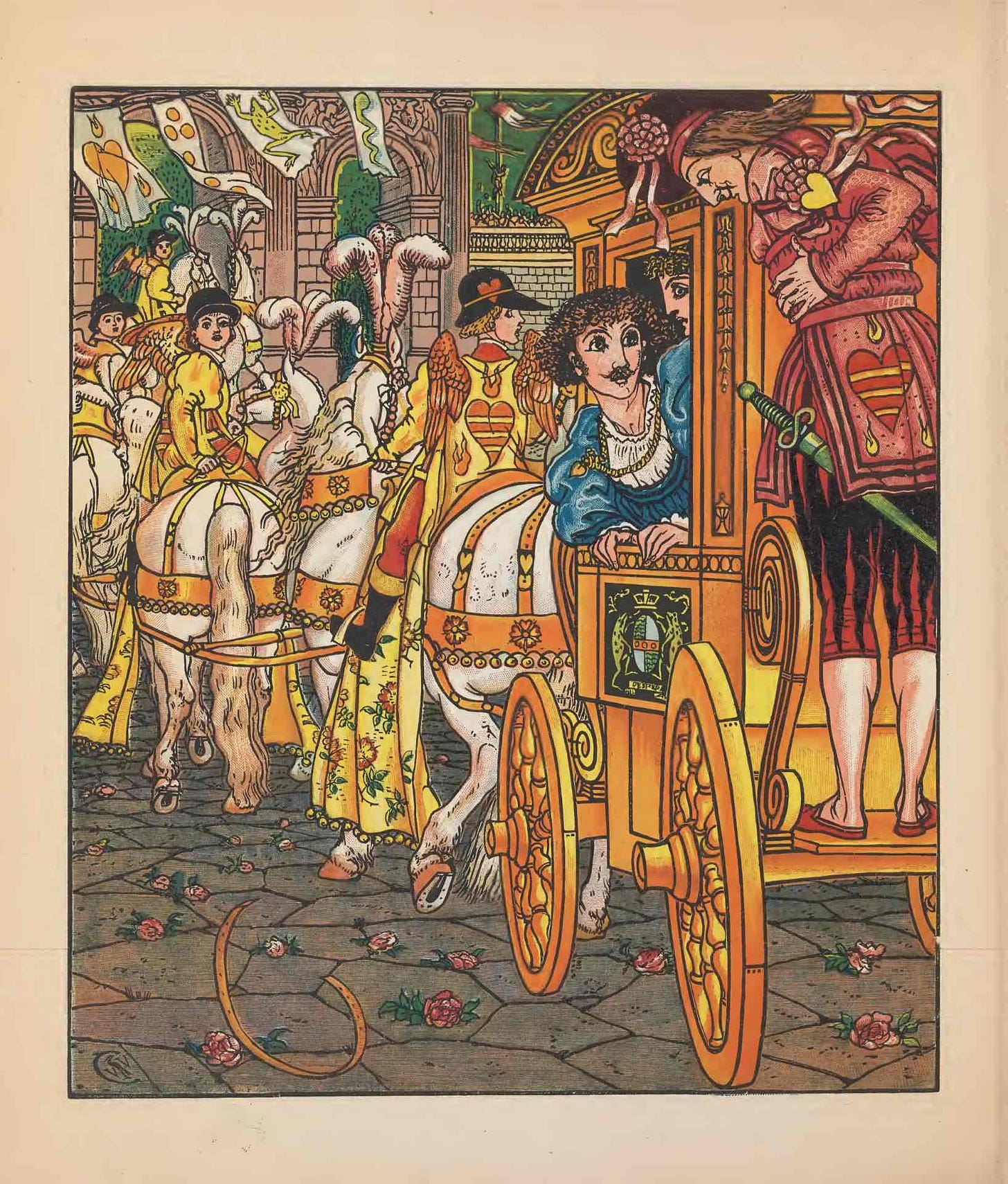

1875 Left art by Walter Crane for Goody Two Shoes. Right is print by Edmund Evans.

The drawing by Crane and the final have one of the more noticeable differences. I’m curious if Crane ended up engraving this one or doing final art on the wood block. I wonder what changes, if any, Evans made. In the final print, Evans has in my opinion greatly enhanced the colors to really uplift this piece. Evans takes the original dark tones and softens them. With Evans' soft touch, he balances the vibrancy of the page and creates areas of great contrast and detail, but also lets other areas rest with flat color or fine texture.

I would also like to know if Randolph Caldecott was influenced by this piece when working on The Diverting History of John Gilpin. It uses similar horseback motion and geese flapping, but to greater effect.

See link to Princeton Blog for details, Left is individual blocks for image on Right.

In this blog by Princeton, We get a fantastic step by step of Edmund Evans’ process to recreate these wonderful watercolors of Kate Greenaway, this process was the same process he used throughout his career, specifically with Walter Crane and Randolph Caldecott as well.

Thomas Bewick and Edmund Evans played crucial roles in the development of children's picture books. Bewick's revival of wood engraving allowed illustrations to be printed with text more easily and cheaply. Evans built on this by pioneering color printing techniques and collaborating with now-famous illustrators to create landmark children's books. Their innovations helped spark a golden age of children's literature.

Reply